David Reeve’s interest in Indonesia began more or less by accident, but he has since become one of Australia’s leading historians within the field of Indonesian studies. He studied French at high school and until then had little knowledge of anything Asian let alone Indonesian. However, after completing university he was accepted to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT).

Whilst at DFAT he was requested to study another language. He suggested maybe Thai or Chinese would be suitable choices, but DFAT instead told him to study Indonesian. “I was sent to a posting in the embassy in Jakarta. That changed my life completely. So it was a very lucky accident,” recalls David.

Whilst at DFAT he was requested to study another language. He suggested maybe Thai or Chinese would be suitable choices, but DFAT instead told him to study Indonesian. “I was sent to a posting in the embassy in Jakarta. That changed my life completely. So it was a very lucky accident,” recalls David.

Before arriving in Indonesia he was sent to the RAAF School of lan- guages at Point Cook. In particular he remembers one sentence while studying there. “I haven’t heard from my elder brother for some time and I am worried that he has been kidnapped by a wild band (gerombolan liar).” Although the training was not systematic, it gave David some first impressions of Indonesia. Then in 1969 when he arrived in Indonesia the embassy sent him to Yogyakarta for three months with one instruction, ‘come back fluent’. He was fortunate to be involved with various student communities while studying in Yogya. Also, the contacts at the Embassy were another source of knowledge about Indonesia. “That was a high quality and high speed education,” David says.

David has seen numerous changes since he first arrived in Indonesia in October 1969. When he first arrived Indonesia was still recov- ering from the remnants of Guided Democracy: bad roads, dismal phone exchanges, unfurnished buildings. People still mostly com- muted by bicycle rather than motorcycle. “So the look of the cities and the towns has been totally transformed,” he reflects. David also believes Indonesia has become far more outwardly Islamic. “Back then it didn’t seem so Islamic; it is much more outwardly Islamic now; I can’t remember any jilbabs,” he says.The political situation has also changed as people have recovered from the trauma and aftermath of the 1965 killings. Whereas, David felt the political system seemed very dangerous at the time, the current democratic system is now “open and rambunctious.” Although a lot has changed David still maintains, “Underneath, it doesn’t seem all that different to me.”

Although he continues to hear of Indonesia’s growing economy he is still somewhat sceptical of what this means in regards to fairness and equality for its people. The political situation is far livelier, but David remains ambivalent about the democratic transformation. Whether as some critics believe it has ‘stalled’, captured by the interest of oli-

garchs, or whether there is room for authentic democratisation. He encourages Indonesian culture to continue to be creative and dy- namic and warns against the “tendency to create a solemn museum culture. Let it rip,” he says.

Having taught in three Australian and six Indonesian universities, David sees little difference between the students in both countries. He believes “the best of them are both frighteningly talented and ac- complished. But in Australia the system helps students to achieve their talents while in Indonesia the students seem to succeed in spite of the system.” He also laments that many Indonesian students will not get the chance of higher education due to a lack of money.

When asked about Indonesia’s upcoming Independence Day, David doesn’t know whether to look back at what has been achieved or to be alarmed at the distance still to go. He cites the work of the great historian Ong Hok Ham who in his later years spoke about what Indo- nesia should mean to his students. Ong would say the alliance of Indonesian feudal princes and Dutch colonialism had left Indonesian society, feudal, stratified and without mobility. He described the period of 1930s as ‘frozen’. David highlights it was Indonesian nationalism that transcended these stratifications. “If it weren’t for the existence of Indonesia, he (Ong) would say to his students, you would all be bowing before traditional princes.” Therefore the existence of Indonesia has opened up new possibilities that could not previously be imagined.

David continues to visit Indonesia three or four times a year and is very grateful for how he ‘accidently’ became interested in Indonesia.

BIOGRAPHY

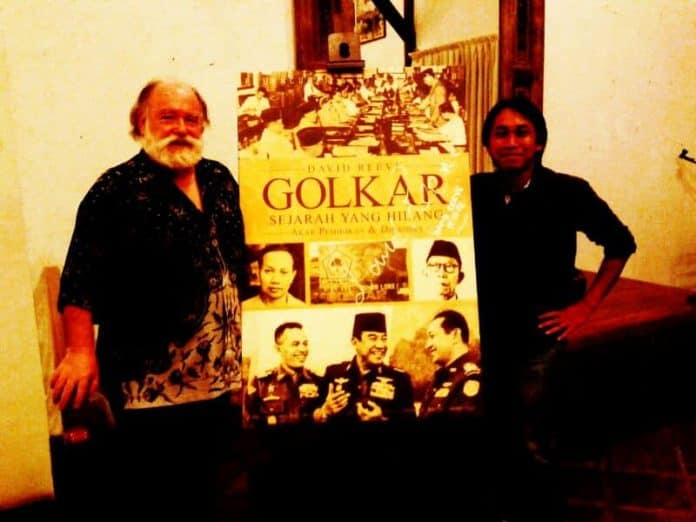

Associate Professor David Reeve was a diplomat at the outset of his career, undertaking Indonesian language training and a posting in Jakarta prior to completing a PhD on Golkar. He was the founding lecturer in Australian studies at the University of Indonesia in Jakarta from 1984 to 1987.

Associate Professor David Reeve was a diplomat at the outset of his career, undertaking Indonesian language training and a posting in Jakarta prior to completing a PhD on Golkar. He was the founding lecturer in Australian studies at the University of Indonesia in Jakarta from 1984 to 1987.

He established Indonesian studies at UNSW in 1990 and was Head of Indonesian/Asian Studies at UNSW until 2006. His biography of Indonesian historian Ong Hok Ham will shortly be pu- blished.He is Deputy Director of ACICIS (the Australian Consortium for In-Country Indonesian Studies), located in Yogyakarta, and was Resi- dent Director from 1997 to 1999.

He visits Indonesia three to four times a year, most recently for the launch of the Indonesian translation of his Golkar book on modern Indonesian political history. He is a frequent speaker at Indonesian studies forums. Currently he is researching the Indonesian diaspora; recent research travel on this topic has included South Africa, Sri Lanka, Suriname and New Caledonia.